No items found.

Anything less than full monitoring of controls leaves room for error - finally you can do away with manual dip sampling. Cable provides automated evidence of your compliance, risk management and

effectiveness, allowing you to:

Why manually test 100 accounts when you can automatically monitor 100%?

Regulators, international standard setters and private sector groups have all started to talk about prioritising financial crime effectiveness over technical compliance. There is growing momentum as more people come to the realisation that financial institutions must be able to prove that what they’re doing is not just legally compliant, but is actually working to reduce financial crime.

The overall message from these organisations is clear, and it is only a matter of time before firms around the world are obliged to demonstrate the effectiveness of their financial crime controls.

Whilst there are clear financial benefits to measuring and evidencing financial crime effectiveness, how to do so remains unclear.

This series provides a deep dive into the world of financial crime effectiveness, covering;

Over the past two decades, the tone from the top has changed on ‘what good looks like’ in fighting financial crime. Regulators, international standard setters and private sector groups have all started to talk about prioritizing effectiveness over technical compliance. There is a growing momentum as more people come to the realization that financial institutions must be able to prove that what they’re doing is not just legally compliant, but is actually working to reduce financial crime.

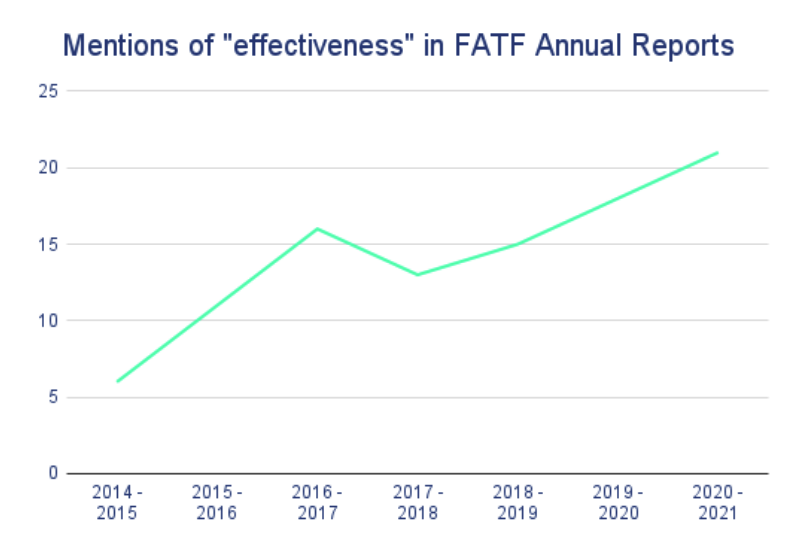

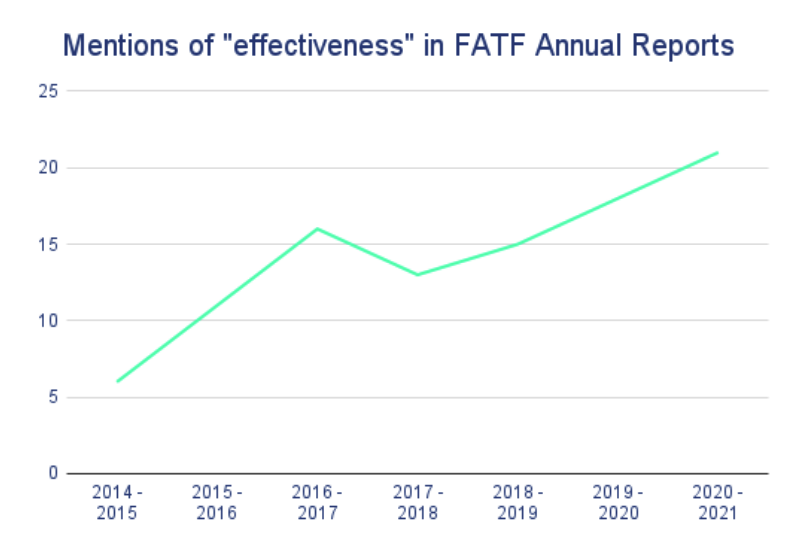

Global direction is shaped by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an inter-governmental body responsible for setting international standards to prevent financial crime. Over time, it has recognized that the components of a financial crime framework must “work together effectively to deliver results” and focus both on effectiveness and technical compliance. Indeed, when carrying out its country assessments, it has stated that “the emphasis of any assessment is on effectiveness”. Since FATF’s methodology is used by other assessment bodies such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, it is very influential in shaping how financial crime systems and programs are appraised.

According to the Wolfsberg Group, an association of global banks which develops financial crime frameworks and guidance, regulators still don’t pay enough attention to whether a firm’s financial crime program is effective, and focus too much on technical compliance. As a result, firms are devoting too much time and effort to ticking boxes rather than trying to detect or stop financial crime. The Group is calling for national regulators to embrace FATF’s approach and assess financial crime programs based on effective outcomes, and have said that firms “should be prepared to explain to their supervisors how their controls actually mitigate risk and/or provide highly useful information to government authorities”.

Although the Wolfsberg Group clearly believes there is still more to do, it is becoming increasingly clear that effectiveness does matter to regulators. Regulators frequently indicate in their public statements that they want to move away from a tick-box approach to one that considers if firms are actually any good at detecting and preventing financial crime. This will lead to a big change in most regulators’ approach to supervision.

The US

In the US, the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has started a massive overhaul of their financial crime program in order to improve effectiveness and utility. In September 2020, FinCEN published an ‘advance notice of proposed rulemaking’ (ANPRM), seeking public opinion on significant regulatory changes and stating that supervision should evolve to “promote effective outputs over auditable processes”. The proposed changes include a new explicit requirement for regulated firms to maintain an “effective” AML program.

It is becoming clear just how important it will be that firms can demonstrate that they are measuring effectiveness, and can explain how they are implementing any new effectiveness requirement.

The UK

Regulators in the UK are also talking more and more about effectiveness, and are likely to follow the Wolfsberg Group’s guidance in calling for more evidence that financial crime controls are actually effective. In a speech in 2016, the FCA recommended that firms should focus on outcomes and reconsider ineffectual processes, saying “If your bank is mired in processes that aren’t effective, do not be afraid to change them”. Once again, the biggest hurdle will be for firms to be able measure their own effectiveness and demonstrate this to their regulators.

So the overall message from all these organizations is clear - financial crime prevention needs to move away from tick box compliance to focus on outcomes and effectiveness. But what does this actually mean, and what does it look like in practice?

The Wolfsberg Group has made the best effort at defining effectiveness, saying that effective controls should:

Point (1) is a given, and whilst it brings us back to tick box compliance, most financial crime professionals agree that pure compliance is still an important element of any effectiveness framework. Points (2) and (3), however, are far from clear.

With the feedback time from government authorities on reported suspicion being many months, if at all, initiating Point (2) would depend on significant structural change within those authorities. Furthermore, finding anyone who is not a lawyer who can define what reasonable means is always a challenge, and with each firm implementing their own risk-based approach, standardizing a measurement of those approaches feels far from easy.

Regulators and government bodies are in agreement that effectiveness is coming, and are already showing signs of building the concept into regulations. It is likely only a matter of time before regulated firms around the world are obliged to demonstrate their effectiveness, and there are certainly huge advantages to them if they can do so.

If firms can measure and evidence the effectiveness of their financial crime controls, they will be able to eliminate ineffective controls, and have much greater flexibility in allocating resources. They will almost certainly be able to move away from manual and laborious processes which do not yield meaningful results, for instance by lowering due diligence requirements for certain low-risk customers or services, or by establishing clearer and more targeted boundaries for transaction monitoring and investigations. However you look at it, effectiveness will reduce the cost of financial crime frameworks.

But how do you measure effectiveness? In the next and final part of this series, we’ll explore the different ways to measure effectiveness, and the pros and cons of each. Read Part 3: How to Measure Effectiveness.

Anything less than full monitoring of controls leaves room for error - finally you can do away with manual dip sampling. Cable provides automated evidence of your compliance, risk management and

effectiveness, allowing you to:

Why manually test 100 accounts when you can automatically monitor 100%?

Regulators, international standard setters and private sector groups have all started to talk about prioritising financial crime effectiveness over technical compliance. There is growing momentum as more people come to the realisation that financial institutions must be able to prove that what they’re doing is not just legally compliant, but is actually working to reduce financial crime.

The overall message from these organisations is clear, and it is only a matter of time before firms around the world are obliged to demonstrate the effectiveness of their financial crime controls.

Whilst there are clear financial benefits to measuring and evidencing financial crime effectiveness, how to do so remains unclear.

This series provides a deep dive into the world of financial crime effectiveness, covering;

Over the past two decades, the tone from the top has changed on ‘what good looks like’ in fighting financial crime. Regulators, international standard setters and private sector groups have all started to talk about prioritizing effectiveness over technical compliance. There is a growing momentum as more people come to the realization that financial institutions must be able to prove that what they’re doing is not just legally compliant, but is actually working to reduce financial crime.

Global direction is shaped by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an inter-governmental body responsible for setting international standards to prevent financial crime. Over time, it has recognized that the components of a financial crime framework must “work together effectively to deliver results” and focus both on effectiveness and technical compliance. Indeed, when carrying out its country assessments, it has stated that “the emphasis of any assessment is on effectiveness”. Since FATF’s methodology is used by other assessment bodies such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, it is very influential in shaping how financial crime systems and programs are appraised.

According to the Wolfsberg Group, an association of global banks which develops financial crime frameworks and guidance, regulators still don’t pay enough attention to whether a firm’s financial crime program is effective, and focus too much on technical compliance. As a result, firms are devoting too much time and effort to ticking boxes rather than trying to detect or stop financial crime. The Group is calling for national regulators to embrace FATF’s approach and assess financial crime programs based on effective outcomes, and have said that firms “should be prepared to explain to their supervisors how their controls actually mitigate risk and/or provide highly useful information to government authorities”.

Although the Wolfsberg Group clearly believes there is still more to do, it is becoming increasingly clear that effectiveness does matter to regulators. Regulators frequently indicate in their public statements that they want to move away from a tick-box approach to one that considers if firms are actually any good at detecting and preventing financial crime. This will lead to a big change in most regulators’ approach to supervision.

The US

In the US, the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has started a massive overhaul of their financial crime program in order to improve effectiveness and utility. In September 2020, FinCEN published an ‘advance notice of proposed rulemaking’ (ANPRM), seeking public opinion on significant regulatory changes and stating that supervision should evolve to “promote effective outputs over auditable processes”. The proposed changes include a new explicit requirement for regulated firms to maintain an “effective” AML program.

It is becoming clear just how important it will be that firms can demonstrate that they are measuring effectiveness, and can explain how they are implementing any new effectiveness requirement.

The UK

Regulators in the UK are also talking more and more about effectiveness, and are likely to follow the Wolfsberg Group’s guidance in calling for more evidence that financial crime controls are actually effective. In a speech in 2016, the FCA recommended that firms should focus on outcomes and reconsider ineffectual processes, saying “If your bank is mired in processes that aren’t effective, do not be afraid to change them”. Once again, the biggest hurdle will be for firms to be able measure their own effectiveness and demonstrate this to their regulators.

So the overall message from all these organizations is clear - financial crime prevention needs to move away from tick box compliance to focus on outcomes and effectiveness. But what does this actually mean, and what does it look like in practice?

The Wolfsberg Group has made the best effort at defining effectiveness, saying that effective controls should:

Point (1) is a given, and whilst it brings us back to tick box compliance, most financial crime professionals agree that pure compliance is still an important element of any effectiveness framework. Points (2) and (3), however, are far from clear.

With the feedback time from government authorities on reported suspicion being many months, if at all, initiating Point (2) would depend on significant structural change within those authorities. Furthermore, finding anyone who is not a lawyer who can define what reasonable means is always a challenge, and with each firm implementing their own risk-based approach, standardizing a measurement of those approaches feels far from easy.

Regulators and government bodies are in agreement that effectiveness is coming, and are already showing signs of building the concept into regulations. It is likely only a matter of time before regulated firms around the world are obliged to demonstrate their effectiveness, and there are certainly huge advantages to them if they can do so.

If firms can measure and evidence the effectiveness of their financial crime controls, they will be able to eliminate ineffective controls, and have much greater flexibility in allocating resources. They will almost certainly be able to move away from manual and laborious processes which do not yield meaningful results, for instance by lowering due diligence requirements for certain low-risk customers or services, or by establishing clearer and more targeted boundaries for transaction monitoring and investigations. However you look at it, effectiveness will reduce the cost of financial crime frameworks.

But how do you measure effectiveness? In the next and final part of this series, we’ll explore the different ways to measure effectiveness, and the pros and cons of each. Read Part 3: How to Measure Effectiveness.